A technical breakdown of freshness, latency, drift, and pipeline desync.

A technical breakdown of freshness, latency, drift, and pipeline desync.

December 7, 2025

•

Read time

We build these magnificent panes of glass, these dashboards, believing they are windows into the living system of our business. We trust them to tell us what is true. Then comes that cold moment of dissonance. The revenue chart ticks upward while the bank account holds steady. The inventory report shows plenty, but the warehouse floor is empty. This is more than a software bug. It is a rupture in the fundamental pact between data and decision-making. Teams are not just misinformed; they are actively misled, steering by instruments that show a world that no longer exists.

The common advice is to "fix the data pipeline," a phrase so generic it is practically meaningless. The real problem is a failure of architectural intent. We have built systems for data collection, not for truth synchronization. Closing the gap requires a surgeon’s understanding of the four distinct pathologies that cause it.

Freshness is not a feature you toggle on. It is a deliberate and costly property you design for. The critical question to ask of any dashboard is this: what moment in time does this actually represent?

Most business intelligence platforms are museums, not live feeds. They display carefully curated snapshots from a past epoch, often yesterday or last hour. The executive looking at a 9 AM dashboard is not seeing the business as it is, but as it was before midnight, a lifetime ago in internet scale. This is the tyranny of the batch window.

The pursuit of true freshness leads you down the path of stream processing and change data capture. But here lies a trap. Many confuse emitting events with achieving freshness. An event stream is a promise of potential freshness, but the real measure is the delta between the event timestamp in your production database and its materialization in the analytical model your dashboard queries. That gap is filled with queues, transforms, and network hops. You must measure this lag as a core system metric. If you cannot graph your dashboard’s data latency, you are flying blind.

Latency is the silent thief of context. It is the compounding delay that lives between the simplicity of an event and the complexity of its meaning. A user clicks a button. That click is an event, fresh to the millisecond. But the dashboard does not display raw clicks. It displays "weekly active users," a derived metric.

To go from click to insight, that event must join with historical session data, filter out bot traffic, apply business rules for geography, and roll up into a time window. Each of these operations is a station on an assembly line, and each station adds seconds or minutes. Your dashboard’s latency is not the speed of the first step, but the sum of all steps. A brilliantly fast stream ingest into Kafka is immediately negated by a sluggish Spark aggregation that runs every fifteen minutes. You have chosen a fifteen minute latency. Own that decision, communicate it, and design your business processes around it. Do not let it be a surprise.

While freshness and latency are problems of time, drift is a problem of logic. It is the most dangerous failure mode because the system appears healthy. Pipelines are green, data arrives on schedule, but the truth has quietly split in two.

Drift occurs when the semantic definition of a concept changes in the production application but not in the analytical pipeline. Imagine your engineering team updates the "purchase" event to include a new validation step in the checkout service. A transaction must pass this new check to be considered valid. The application logic changes instantly. But the data team’s transformation code, that SQL query buried in a dbt model that powers the "Daily Sales" dashboard, still counts every transaction from the orders table. For weeks, the application and the dashboard disagree on the foundational question of "what is a sale?" and no one knows.

Drift is a failure of communication and contract. It reveals that your application codebase and your analytical codebase are two separate kingdoms, each with its own laws, and no ambassador passes between them. The only antidote is to treat data definitions as a first class API, with all the discipline, versioning, and breaking change management that implies.

Our data architectures are built on a tower of abstractions. A production database writes a row. A CDC tool scours the transaction log and publishes a message. A stream processor consumes it, applies a transform, and writes to a data warehouse. Finally, a BI tool queries that warehouse.

This decoupling is powerful, but it introduces a terrifying possibility: selective amnesia. Each component has its own failure mode. The CDC connector might crash and miss a thousand transactions before restarting. The data warehouse might have a compaction job that fails silently. The transformation might have a null pointer error that discards records from a specific region.

The result is a dashboard that is not entirely wrong, but partially correct. It is a plausible lie. These are the hardest errors to detect because they do not throw alerts. They require a separate system of verification, a reconciliation process that constantly asks the painful question: does the sum of parts in the data warehouse equal the whole in the production system?

Closing the gap is an exercise in engineering discipline, not just tool selection. It begins with a shift in perspective. You are not building a dashboard. You are building a truth synchronization system with a dashboard as its output terminal.

First, you must institute rigorous Service Level Objectives for your data products. Define the maximum acceptable freshness latency for each key metric. Define the allowable error bound for financial reconciliation. Monitor these SLOs with the same fervor you monitor application uptime. A breach here is a breach of trust.

Second, you must formalize the handshake between production and analytics. Implement data contracts that are codified, version controlled, and tested. The team that owns the "purchase" service must also own the canonical definition of a "purchase," and the analytical pipeline must consume that definition as a dependency. This is how you kill drift.

Third, design for observability and repair. Assume every component will fail. Can you see the lag? Can you replay the events? Your pipeline must be as observable as your application, with traces that follow a single transaction from the UI click through the Kafka topic, the transform, and into the dashboard tile. And when you find a gap, you need idempotent, repeatable backfill processes to heal the wound, not ad hoc scripts that create new problems.

Finally, match the architecture to the need. Not every metric needs to be real time. The CEO’s strategic dashboard might be perfectly served by a nightly batch of impeccably clean, reconciled data. The fraud detection system needs seconds. Use a hybrid approach. Apply streaming for the core pulses of the business that demand immediacy. Apply batch for the complex, large scale historical synthesis that demands precision. The clarity of this choice is what separates a reactive data pile from a coherent information system.

A dashboard that has drifted from production is not a technical inconvenience. It is a strategic liability. It means the organization is having a debate about what to do next based on different versions of reality. Our role as engineers and architects is to build systems that collapse those distances, that bind the digital perception to the operational truth. We do not need more data. We need more trustworthy data. The goal is alignment, so that when the dashboard moves, everyone can be confident the world just changed.

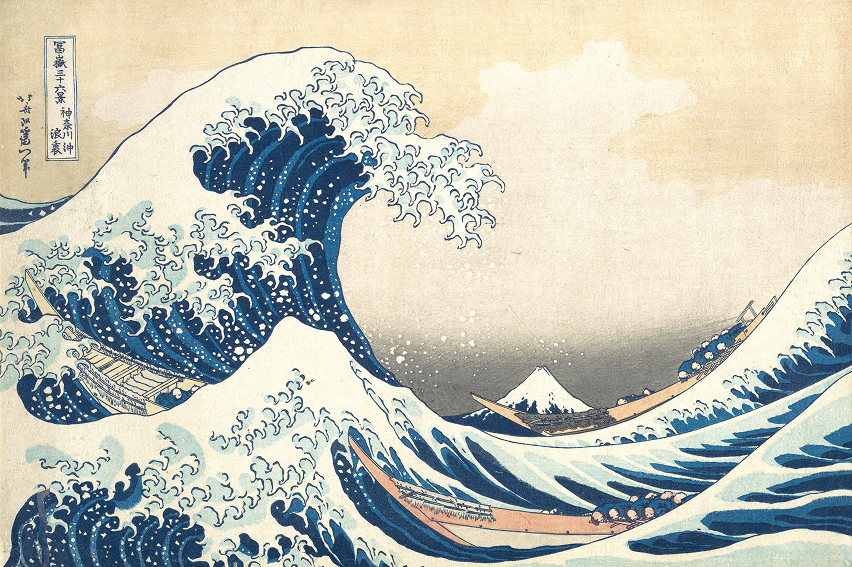

About the Art

Diego Rivera’s The Weaver (1951) stood out because of its focus on precision. A tapestry works only if every thread stays in the right order. A slight shift early in the pattern creates a visible distortion later, long after the mistake is made. That idea mirrors the relationship between production and dashboards. When the upstream threads fall out of alignment (missing events, outdated definitions, quiet latency), the downstream fabric tells a different story. The painting captures that kind of structural fragility with a simplicity that fits the article.

Credits: © 2018 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Why small ingestion errors turn into downstream incidents if you don’t test them at the source.

How the hidden weight of governance burnout shapes risk culture and alignment.

The shift from manual audits to reflexive architecture. How to build systems that monitor and correct their own compliance policies.